Not long before he died, Grandad said something that I thought was a little silly, a little old-fashioned.

He declared that he didn’t trust the banks, and he didn’t want them to know what he did with his money. I scoffed at the time, paranoid old fella! But of course, it turns out I owe him an apology.

As we were walking around his house, he motioned toward an off-white wall with an off-comfortable sofa in front of it. This piece of singularly ugly furniture hadn’t left its spot in more than a decade.

The wall had a small square door that, when pushed in, revealed a crawl space. Inside was packaging from the 1970s, partially gnawed board games and unimportant documents, squirreled as if they would one day stave off a harsh winter.

My Grandad guided my flashlight to a brown padded envelope hidden near what I was truly hoping wasn’t exposed asbestos. I retrieved the envelope and handed it over. He took the opportunity to deliver a short speech. He was proud I was doing my Master’s, and he knew it was a financial burden, so he wanted to help. Inside the envelope was a musty wad of cash fastened with a mostly decayed rubber band.

His speech was meaningful, but what came after was wisdom that took more than 10 years to land. I asked why he hid cash in the wall, and he explained that most of his savings were hidden around the house; in books, in wardrobes, under mattresses. In fact, he joked that when he died, I must tear the house apart before it’s sold.

Well, he did die, and we did examine every crack and cavity, and we did indeed find most of his savings. Some of the cash was so old that we worried the bank may not even agree to exchange it for modern legal tender, though inflation had robbed the piles of most of their purchasing power anyway, two scams of fiat that I’ll save for another article.

My Grandad grew up poor in wartime London, and it meant a fierce caution with currency was woven into his DNA; money was scarce. Still, his philosophy was sound, and it has played on my mind for years now.

The people of my grandparents’ era were highly protective of their privacy, back when it was a basic human right. I know, how quaint.

In 1950, a motorist named Harry Willcock was stopped in London, and the police officer demanded to see his identity card, an unfortunate requirement introduced at the outbreak of World War II.

Harry refused to brandish his papers and was arrested. According to the lord chief justice in charge of the subsequent legal battle, the ID cards were now being used for purposes beyond their original scope. And so, they were scrapped.

Back in the 1950s, privacy was the baseline for most, and it led to suspicion of anything like surveillance, despite there not being much of it. Just 70 years ago, surveillance was rare, labor-intensive and expensive, typically involving someone physically following you, possibly in a trench coat.

Conversations, cash payments and public transport; no permanent record was left. Any records created were mainly on paper and, importantly, siloed. You couldn’t easily cross-reference records; it’s what lawyers call “practical obscurity.”

Today, our data is farmed, sold and cross-referenced en masse as surveillance has become the new baseline.

My Grandad would have loathed the modern way. He was unknowingly a cypherpunk, and those values are eroding with increasing speed.

Privacy, self-sovereignty, decentralization: Before it’s too late

The privacy narrative that has arisen of late could be chalked up to numerous causes, but it feels like a desperate and inevitable last stand.

Society is somehow so downtrodden that tools to assist with privacy are demonized. Vitalik Buterin used a mixer to donate money and was criticized with winks and nods, suggesting he was shady for doing so. Buterin replied with the simple yet iconic, “Privacy is normal.”

There is a sense that a desire for privacy must mean you have something to hide, but as Susie Violet Ward, CEO of Bitcoin Policy UK, once replied: “You have curtains in your house, don’t you?”

Eric Hughes wrote in “A Cypherpunk Manifesto” in 1993 that “privacy is necessary for an open society in the electronic age. Privacy is not secrecy. A private matter is something one doesn’t want the whole world to know, but a secret matter is something one doesn’t want anybody to know. Privacy is the power to selectively reveal oneself to the world.”

Self-sovereignty has followed the downward trajectory of privacy. Control over one’s identity, data and even property has been steadily stripped away, year after year. We must offer up identification, in nearly a “papers, please” kind of way, to most centralized authorities with which we wish to interact.

With data, extensive legal battles have carved us a sliver of control with the “right to be forgotten,” but even that still requires each person to manually request the erasure of their data from each holder.

Likewise, with property, the “right to repair” was necessary as manufacturers of everything from cars to phones raised the walls of their gardens.

These issues are not the concern of the unscrupulous, and we need not whisper. Privacy is normal, as is agency over the many threads of our lives and the right to a fair, pragmatically decentralized playing field.

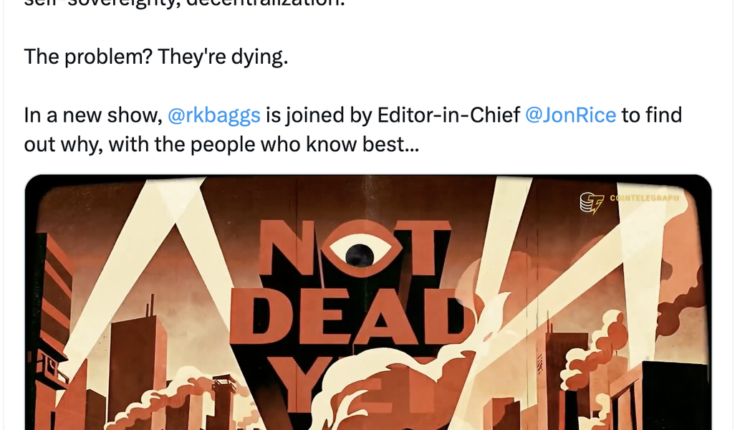

That is why Cointelegraph is launching a show dedicated to conversations on the erosion of these basic human rights, with bona fide experts, visionaries and those building the tools of a free and private future. It is a show for the digital dissidents who believe in civil liberties.

Because cypherpunk values are dying.

But they’re Not Dead Yet.

Not Dead Yet will air weekly from Thursday January 8th, and some of the biggest names in cryptography, privacy, and decentralization will be joining Robert Baggs to explore how these values survive in an increasingly centralized, surveillance-oriented version of society.